On July 16, 1941 Chisinau was occupied by Romanian troops together with units of the 9th Army of the Wehrmacht. Along their way they annihilated the Jewish population.

The exact number of Jews remaining in the city is not known. Some were deported by the Soviet government before the war; some were evacuated or drafted into the Red Army. The rest could not imagine what awaited them in the future.

On July 24, 1941 the governor of Bessarabia, General Voiculescu issued an order to create camps for Jews from the countryside and establishment of the Chisinau ghetto.

The ghetto depended on the military commandant of the city: Colonel D. Tudosie (18.07 – 1.09.1941), General Panaytiu (1.09 – 7.09.1941) and Colonel E. Dumitrescu (7.09 – 15.11.1941).

The ghetto depended on the military commandant of the city: Colonel D. Tudosie (18.07 – 1.09.1941), General Panaytiu (1.09 – 7.09.1941) and Colonel E. Dumitrescu (7.09 – 15.11.1941).

In his first and most famous speech for the ghetto population, Tudose said: “Kikes, from today you are the slaves of the great Romania. Those who will not follow orders, will be shot…”.

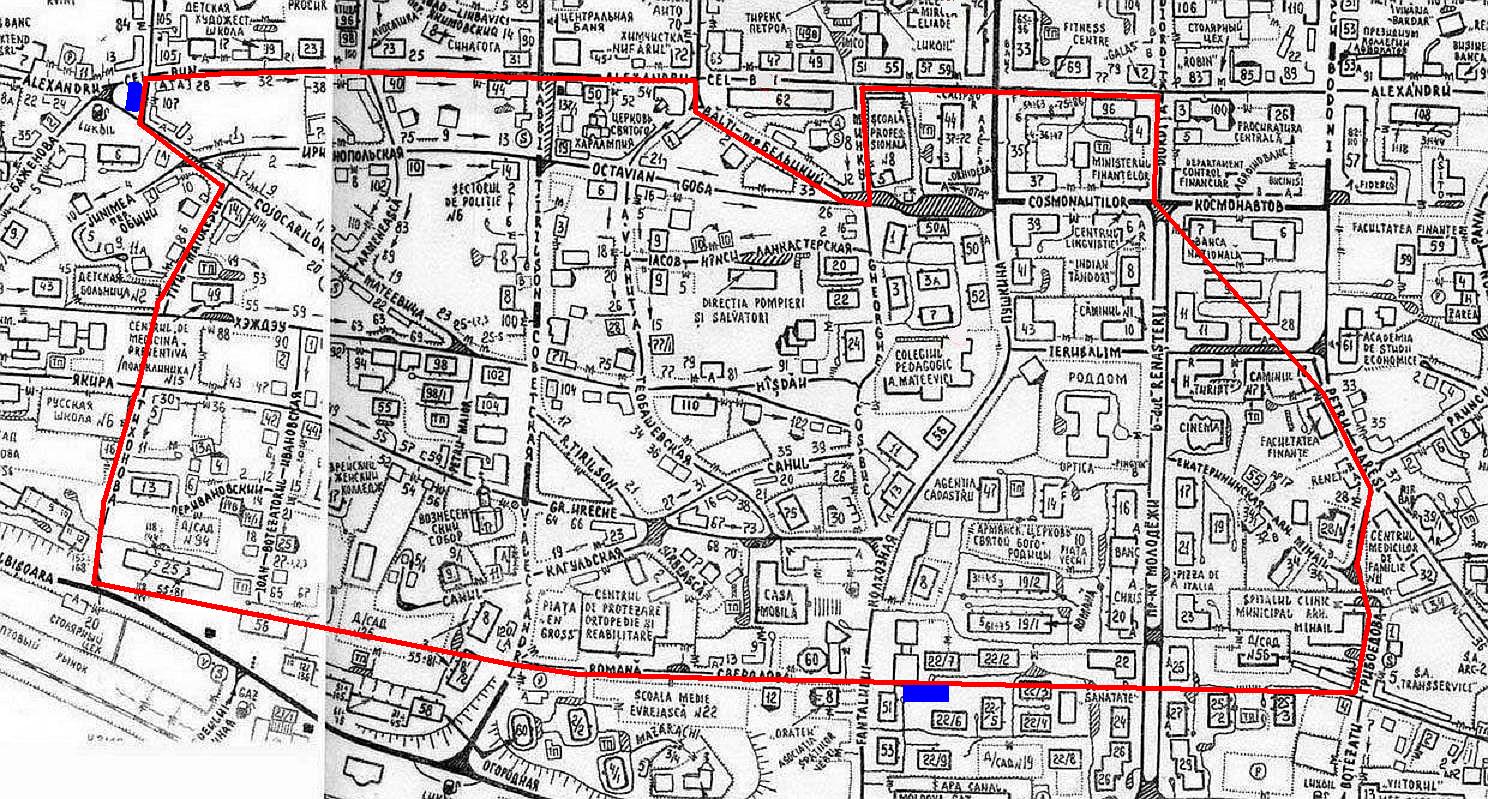

The ghetto was established in the lower part of the city (before the war the p9opluation here was predominantly Jewish),

The ghetto was established in the lower part of the city (before the war the p9opluation here was predominantly Jewish),

There were two entrances to the ghetto. The wooden fence along the perimeter was four kilometers length. At first they were guarded by 80 soldiers, later this number was increased to 250.

Only two days have been allocated for the resettlement of thousands of people. They were expelled from their homes, and allowed to take only what they could carry. They settled where they could find a place, in one house or even in one room 25 people could accommodate. The inhabitants of the ghetto were forbidden to leave it.

From the memories of the survivor Samuel Aroni

From the memories of the survivor Samuel Aroni

“All of us, parents, brother, grandmother, uncle, aunt and her sister were driven from our house on Thursday morning, July 24, 1941. We went to my grandfather’s house, Aaron-Josef Chervinski. A few hours later, two Romanian soldiers came and robbed us. They threatened to kill us, but left. I remember my thoughts very well. I am 14 years old; at that moment I was sure that I would die. In the evening, fearing that the soldiers would return, we went to the ghetto and found a room. Later, the soldiers returned to my grandfather and dragged him by the beard to our new home.

Despite suffering, my grandfather, a very religious Jew, spent the night praying on the eve of the new Jewish month. When I close my eyes, in the dark I see my father and myself next to him praying in honor of the new moon.”

The specificity of the Chisinau ghetto was that about 100 Christian families were not evicted from the territory, they received special entry and exit permits. There were also containers for storing grain and corn, plants for soap, siphons and ropes production. The road to the airport passed through the entire ghetto. All this complicated control of the authorities, but on the other hand, it saved some Jews.

The prisoner of the ghetto, I. Lyudmer, was able to escape on October 23, 1941, with a great risk; she went to her friend Sofya Christie. The next seven months Lyudmer hid in her house. Christie gave Lyudmer her papers, and so she escaped.

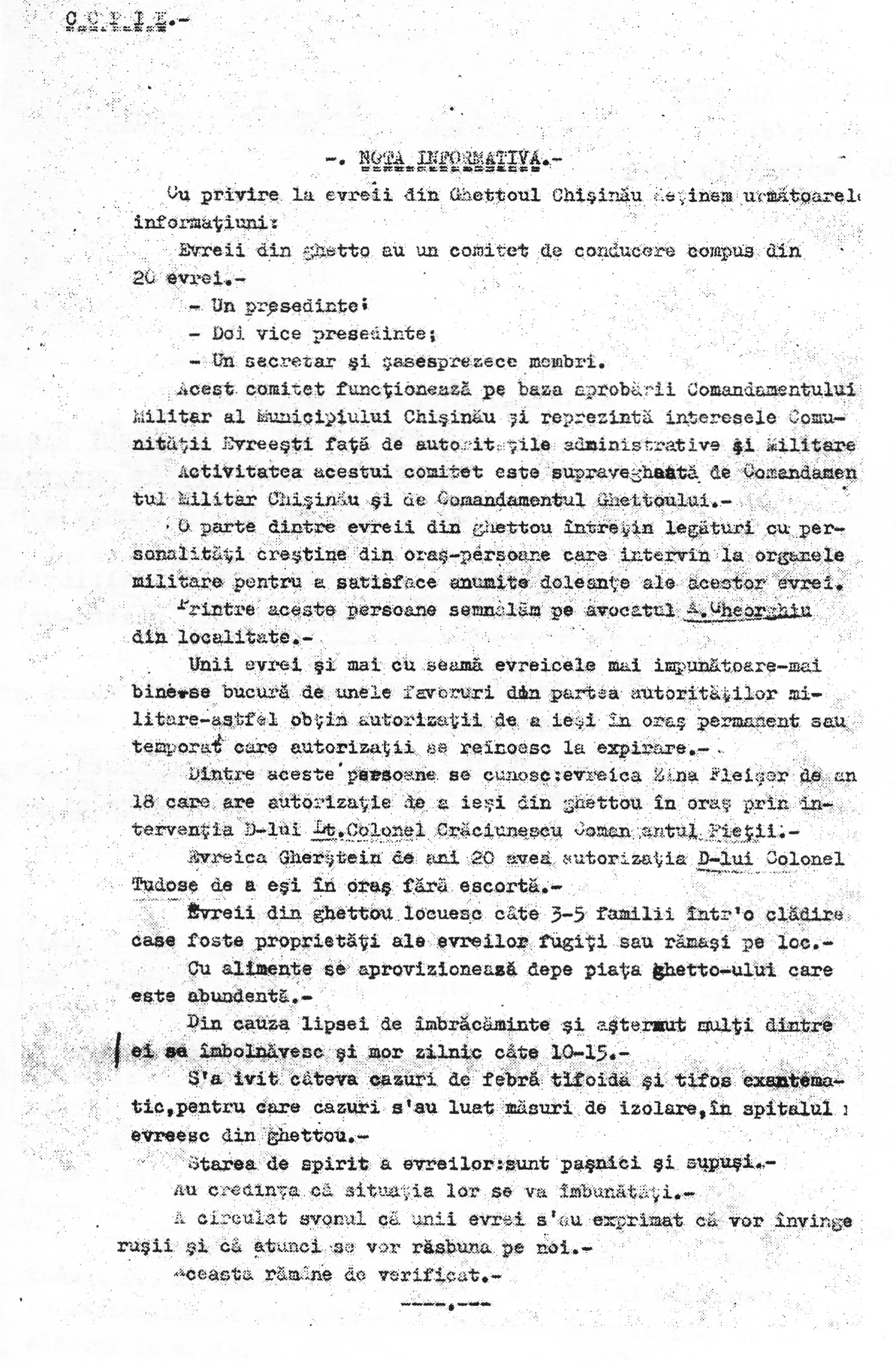

At the end of July, the Romanian authorities created a committee of 22 people in the ghetto. It was headed by Dr. G. Landau, and the lawyer A. Shapiro’s became his deputy. The committee set up a bakery, a hospital and organized a market and kitchen work, which released about 200 meals a day, tried to improve situation of people through Bucharest Jews (products and money were received from Bucharest, where the Jewish community headed by the doctor V. Filderman took care of the Chisinau ghetto inhabitants). On September 11, an orphanage was opened for 28 orphans.

At the end of July, the Romanian authorities created a committee of 22 people in the ghetto. It was headed by Dr. G. Landau, and the lawyer A. Shapiro’s became his deputy. The committee set up a bakery, a hospital and organized a market and kitchen work, which released about 200 meals a day, tried to improve situation of people through Bucharest Jews (products and money were received from Bucharest, where the Jewish community headed by the doctor V. Filderman took care of the Chisinau ghetto inhabitants). On September 11, an orphanage was opened for 28 orphans.

As soon as the hospital was somehow equipped, on the order of the commandant of the ghetto, all the beds, linen and medicines were taken from it. The community opened a second hospital.

The ghetto population was actually doomed to starvation. The commandant of the ghetto prohibited selling products to the Jews until 11 am, and after this hour they could no longer be obtained. The number of deaths caused by malnutrition and illnesses reached 10-15 per day, and were included in the reports as “death from a natural cause”.

The ghetto population was actually doomed to starvation. The commandant of the ghetto prohibited selling products to the Jews until 11 am, and after this hour they could no longer be obtained. The number of deaths caused by malnutrition and illnesses reached 10-15 per day, and were included in the reports as “death from a natural cause”.

Some peasants, neglecting risks, brought food.

The Jews were left to their fate and sold their things on the market; it was practically the only way of survival.

In the mornings, Romanians and Germans came to the ghetto and took men, women and children for domestic works. Employers not only did not pay them, but did not feed either. The commandant noted disobedient and at the first opportunity the “guilty” disappeared forever.

At 8 pm the life in the ghetto completely died down. None of the prisoners had the right to leave the dwelling.

At 8 pm the life in the ghetto completely died down. None of the prisoners had the right to leave the dwelling.

Before the organization of the normal guard system of the ghetto, drunken officers and soldiers often broke into the houses at night, raped the girls in front of their parents, took away their belongings and disappeared.

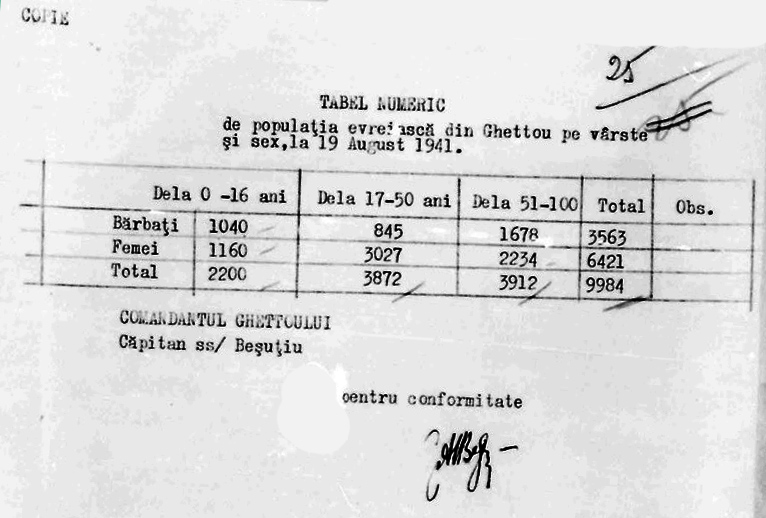

According to the data from Aug 19, there were 9,984 Jews in the ghetto (2,523 men, 5,261 women, 1,160 girls and 1,040 boys). In the middle of September, there were almost a thousand more people in the ghetto. Of the 11,525 prisoners, there were 4,168 men; 4,476 women and 2,901 children. The increase in the population was due to the fact that Jews from the surrounding settlements were gathered in the Chisinau ghetto. Since August 5, Jews of the city were required to wear a six-angled star.

Most of the inhabitants of the ghetto were poor. Own means were possessed by about 2,000 Jews, of which only 200 could be considered rich. Therefore, most of them received money for life, selling things and utensils.

Most of the inhabitants of the ghetto were poor. Own means were possessed by about 2,000 Jews, of which only 200 could be considered rich. Therefore, most of them received money for life, selling things and utensils.

In August, mass executions began. On Aug 1. 411 prisoners were shot near the station of Visterniceni, on Aug. 7 325 Jews were executed in Gidigich.

In August, mass executions began. On Aug 1. 411 prisoners were shot near the station of Visterniceni, on Aug. 7 325 Jews were executed in Gidigich.

The situation of the Jews in the ghetto contributed to the fact that a large number of scammers tried to take advantage of this situation and bought jewelry from the victims (this violated instructions to surrender it to the bodies of the National Bank of Romania and led to punishment).

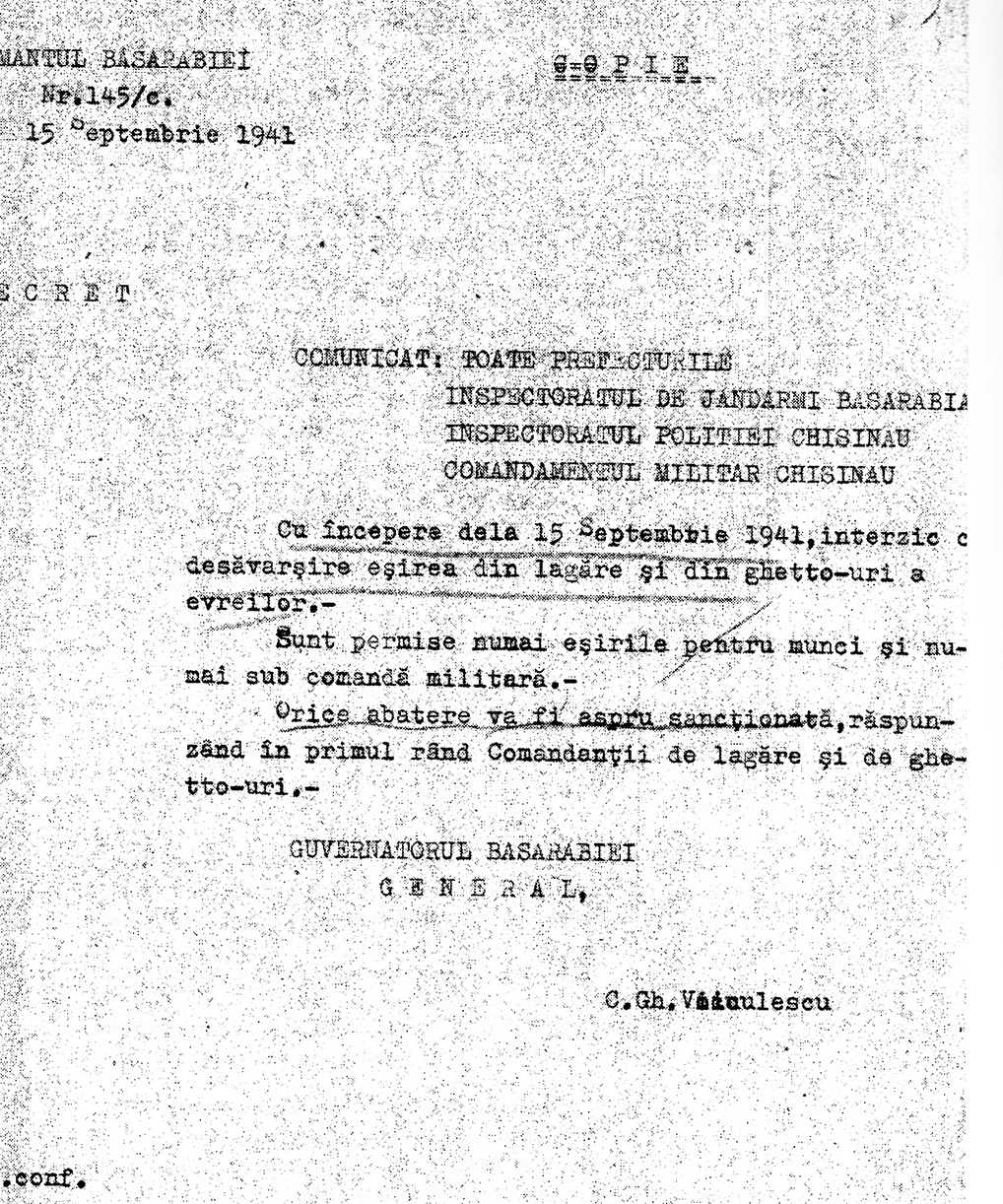

The illegal trade of permits to enter the city and postpone deportation was widespread. This happened exclusively through Colonel E. Dumitrescu and his lover N. Terzi, who had access to the ghetto. She set the price for going to the city and for deferring deportation.

The illegal trade of permits to enter the city and postpone deportation was widespread. This happened exclusively through Colonel E. Dumitrescu and his lover N. Terzi, who had access to the ghetto. She set the price for going to the city and for deferring deportation.

For example, a resident of the ghetto received 3-4 deferments of deportation, paying for them a diamond ring worth 72,000 lei, Mura Volovet and Ida Spanerman paid 5,000 lei each plus a coat with a lining and a fur collar for three permits.

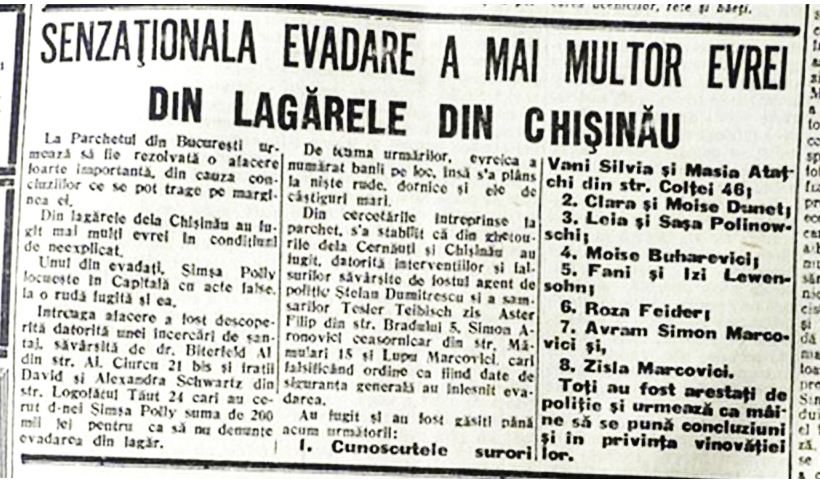

Rich Jews, who had currency and jewels, tried to bribe Romanian and German officials in order to move to Romania. Officials accepted offerings, and then, as a rule, gave them to the authorities. In the newspaper “Basarabia” dated April 24, 1942, examples are given of the searches of Jews who fled the Chisinau ghetto for Bucharest. But there have also been cases of fulfillment of promises. Composer Eugene Coca, forging a certificate of baptism, obtained the release from the ghetto of his son-in-law Emanuel Printsevsky.

Rich Jews, who had currency and jewels, tried to bribe Romanian and German officials in order to move to Romania. Officials accepted offerings, and then, as a rule, gave them to the authorities. In the newspaper “Basarabia” dated April 24, 1942, examples are given of the searches of Jews who fled the Chisinau ghetto for Bucharest. But there have also been cases of fulfillment of promises. Composer Eugene Coca, forging a certificate of baptism, obtained the release from the ghetto of his son-in-law Emanuel Printsevsky.

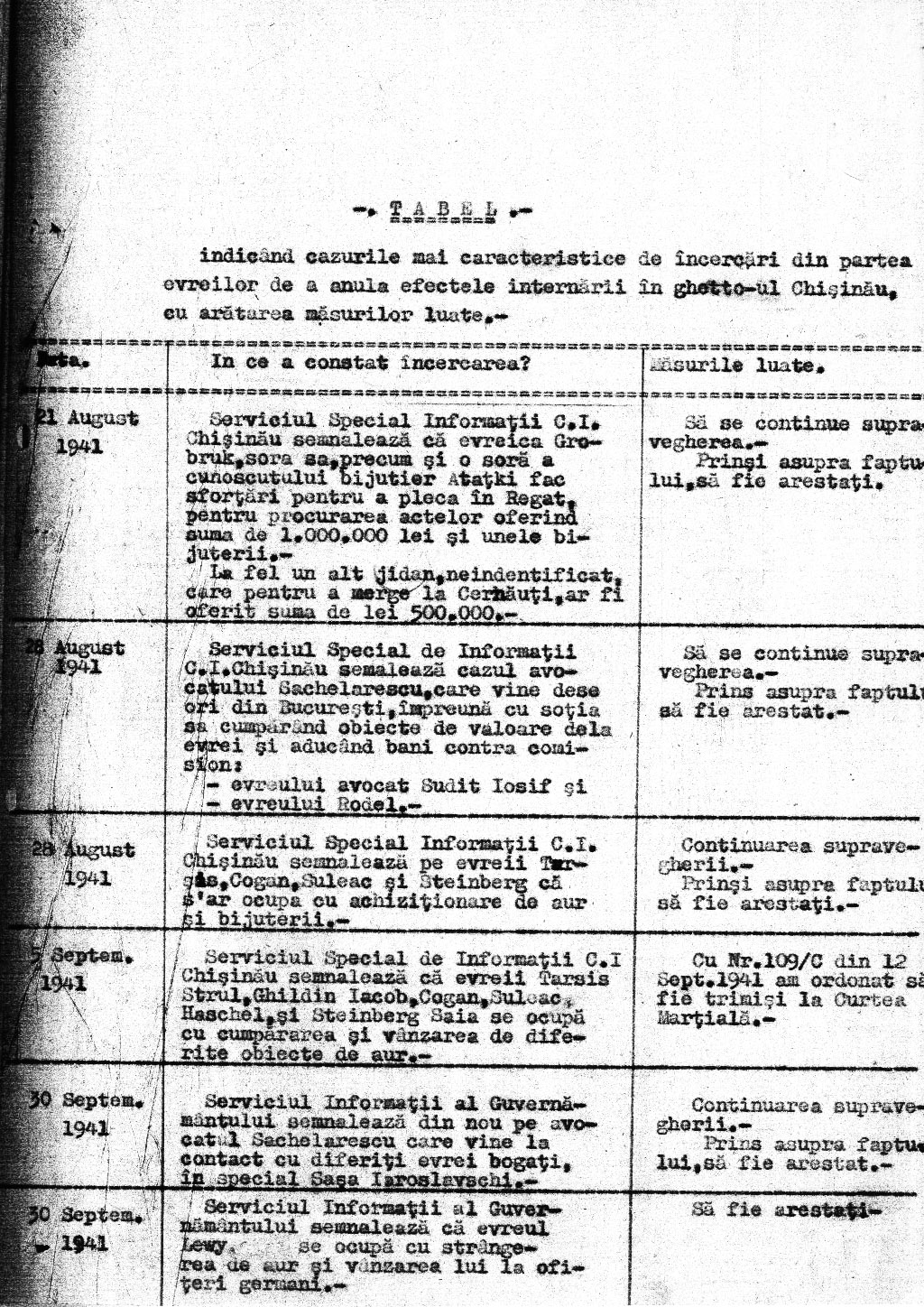

Extracts from the Chart, showing cases of attempts by Jews to violate the rules of internment in the ghetto of Chisinau with the measures taken.

Extracts from the Chart, showing cases of attempts by Jews to violate the rules of internment in the ghetto of Chisinau with the measures taken.

August 21, 1941

The special information service of Chisinau informs that Jewish woman Grobuk, her sister and sister of the jeweler Atatsky make efforts to leave for Romania, to purchase documents worth 1.000.000 lei and jewelry.

Another unidentified Jew offered an amount of 500,000 lei for his departure to Chernovtsy. Continue observation. Arrest in case of capture.

September 30, 1941

The intelligence service of the government reports that the Jew Levy is collecting gold and selling it to German officers. Will be arrested.

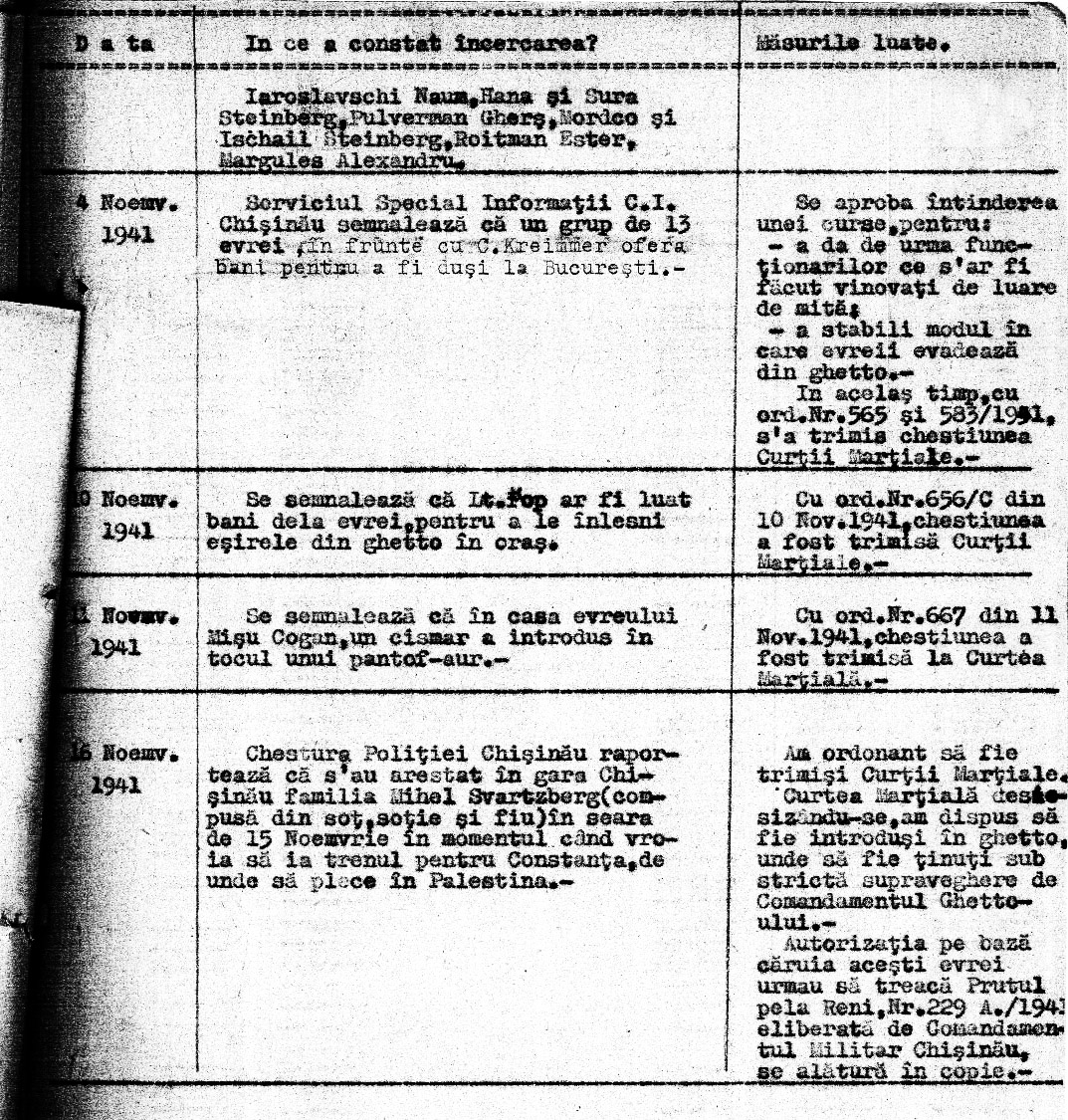

November 4, 1941

November 4, 1941

The special information service of Chisinau informs that a group of 13 Jews headed by S. Kreimmer offers money for moving to Bucharest.

Approve the following measures:

– The employees will be punished for taking bribes

– Determine conditions for the evacuation of Jews from the ghetto

November 16, 1941

The main police department of Chisinau informs that on the evening of November 15 at the Chisinau station the family of Michel Schwarzberg (consisting of husband, wife and son) was arrested at the moment when they wanted to get on the train to Constanta, from where they were planning to go to Palestine.

It is ordered to be sent to a military court. The military court decided to return them to the ghetto under the commandant’s supervision. The permission by which these Jews could cross the Prut in Reni No. 229 A. / 1941 issued by the military commandant of Chisinau is attached in a copy.

From the very beginning, the ghetto was considered a temporary refuge for the Jews. The purpose of the Romanian authorities was to “cleanse” Bessarabia and Bukovina of “the Jewish elements” via mass deportations across the Dniester. The deportation began on October 8, 1941, when 2,500 people were brought out.

Sources used: Materials of the National Archive of the Republic of Moldova (ANRM), www.oldchisinau.com

Project ” The Holocaust unhealed wounds” with support Yad Vashem- the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority and the Genrsis Philanthropy Group.