Om February 24 the 75th anniversary of the tragic death of 103 kids, 269 women and 417 men on “Struma” ship is marked.

Romanian Jewish refugees had only one way – via the war-torn Black Sea to the Turkish of Bosporus and Dardanelles and further crossing the Mediterranean Sea to Palestine.

Preparing of the refugees transport began in September 1941 with the publication of newspaper advertisements. At the same time an old Bulgarian motor sloop “Struma” was chartered. It was launched in 1867 and in 1937 its modernization was carried out. The sloop was converted into a passenger ship with tiny cabins and 8-10-tiered bunks, rescue means were limited to two old boats.

Preparing of the refugees transport began in September 1941 with the publication of newspaper advertisements. At the same time an old Bulgarian motor sloop “Struma” was chartered. It was launched in 1867 and in 1937 its modernization was carried out. The sloop was converted into a passenger ship with tiny cabins and 8-10-tiered bunks, rescue means were limited to two old boats.

Initially, the cost of ticket was 30 thousand Romanian lei (about 100 US dollars) per person. On the eve of departure the price grew by 10 times.

On December 12 the ship with about 800 pasengers and 10 people of Bulgarian crew under the Panamanian flag left the port of Constanta.

Immediately the engine failed. Passengers gave their gold rings and watches to call a team of repairmen from Constanta.

The vessel continued its way, and in the evening on December 14 reached the Bosporus. However, the diesel stalled again. Drifting on the busy sea route, the captain ordered to pay the anchor and raised alarm about the accident.

Turkish authorities tried to do all to get rid of the unwanted vessel. It was taken in tow and set aside on a raid in Istanbul. In the morning the mechanics crew arrived: the engine was not subject to restoration.

On December 20 “Struma” was placed in quarantine. The boat of the Coast Guard was on duty to prevent connectons with the shore. Turkish authorities notified the British Embassy (as a country, in the mandated territory of which “Struma” was directed) and Romania (the country of freight).

Romanian consul said that he no longer considered “Struma” passengers as Romanian subjects; actually saving them from possible deportation. The British ambassador in Istanbul sent a proposal to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs “to allow the refugees to continue the path to Palestine, where they, despite the illegal status could receive human treatment.”

The Turkish government has banned the movement of refugees on its territory, but was ready to help send them to Palestine, if the British would agree to accept them. British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden expressed his “disappointment” by the position of Ambassador and noted that “we did not need these people in Palestine.” The High Commissioner of Palestine, Sir Harold McMichael said that many of the refugees from the “Struma” were not the “owners of the necessary professions” and would be “counter-productive element in the population.” It is also necessary “to prevent the penetration of Nazi agents under the guise of refugees”, so – do not let anyone.

The situation in the “Struma” was catastrophically deteriorating. Provisions stocks ran out. To attract the attention the refugees have made posters «SOS» and “Help us!” of sheets and hung them on the ship sides.

About what was happening it became known through Medea Salamovich, who was evacuated to the hospital with “Red Cross” help due to pregnancy aggravation.

Captain ordered to share the crew stocks, but this could only last for a short time. In the crowded and unsanitary conditions in an unheated hold infections and colds began. There were no medicines.

The fate of the Jews stopped at Istanbul, was described in the local press and the world’s leading publications. Simon Brod, a local Jew and businessman using his connections, delivered on board food and medicine.

In January five passengers who had old British visa the ship were allowed to leave the ship. Until February 23 about 20 refugees left the board.

Fearing a complication of relations with Germany, the Turkish government has demanded from British consent or refusal to transport the refugees to Palestine, and receiving no answer, decided to bring the ship back to the Black Sea.

On February 23 “Struma” with the cut anchor rope was removed from the Bosporus Strait. It drifted along the coast at a distance of 9 to 4 miles. Despair and fear reigned on the board.

On the morning of February 24 there was an explosion, and the ship sank. Most likely it was a torpedo released from Sch-213 Soviet submarine under the command of 27-year-old lieutenant Dmitry Denezhko. Most of the passengers perished from the explosion. But about a hundred people were alive; they were holding large fragments of the ship, in the icy water, one after another disappearing into the depths.

At the time of death 103 children, 269 women and 417 men, including Bulgarian sailors were on board.

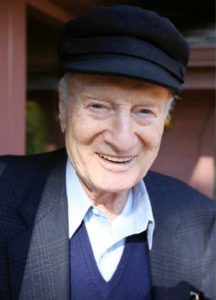

Only one of all managed to escape. His name is David Stolyar.

He was born in 1922 in Chisinau. Five years later, his family moved to Paris. After another five years, the family returned to Romania, his parents divorced, and the mother and son left for France. Later, David returned to his father in Bucharest, where he was expelled in 1940 from the Lyceum and sent to a forced labor camp because he was a Jew. In July 1942 Bella Stolyar was arrested and sent to Auschwitz, where she died. Yacov, the father, had money and some connections and was able to release his son from the camp and buy him a ticket to the “Struma”.

“I woke up; I was thrown into the air. I fell into the water, and when it came up – there was no ship. Nothing. Only fragments,”- recalled 19-year-old boy.

Only in the evening, David discovered another alive person – captain assistant Lazar Dikov.T they huddled together and cried all night not to fall asleep. A day later, Dikov fell into the water and drowned.

A few hours later a boat approached and saved David. He was taken to the hospital, in a week – in jail for illegal stay on the territory of Turkey. In 71 days he was released. With Simon Brood’s help David got to the Land of Israel. As part of the British army served in Jerusalem, Baghdad, and Cairo. He married an Egyptian Jewish girl Adrie, fought in the War of Independence, sought out and took his father to Israel.

In 1961 his wife died, 16 years David had not told her about the tragedy on “Struma”. After leaving Istanbul, the only one to whom he spoke about what had happened, was a British intelligence officer who interrogated him upon arrival in Tel Aviv.

In 1968, David married for a second time. Two years later, he told his wife about the “Struma”. Then the whole world learned about the tragedy at the Turkish coast.

On May 1, 2014, David passed away

“You know, I think I just got lucky. Yes, pure luck. No other explanation for this can be given. “