Time is what makes us look back, go deeper into the details of the past, peering under a microscope or, conversely, trying to see it through binoculars. How often do we notice that we were inattentive and not curious enough about the stories of loved ones about their lives, joys and sorrows, family and connections, did not torment them with questions, looking at faded photographs: “Who is this? And this?” We thought we were going to live forever with our parents, leaving for later learning about the family history and everything connected with it. And now, when they are gone, and we have arisen an interest, there is no one to satisfy it…

In June 2022, it was 100 years from when my father was born in the small Bessarabian shtettle of Briceni. They called him Borukh – blessed one.

Let us try to move to that time and imagine the place and family where he was born. Briceni was a typical shtettle where Jews – mostly artisans and small traders and peddlers – made up the majority. There were many synagogues, welfare organizations, a Jewish hospital; community life was in full swing.

My father’s grandfather – Aron – was engaged in trade. He had a grocery store. It was located on the first floor of a two-story house, and the family lived, as was customary, on the second. Aron and his wife Malka had five sons and five daughters. Among them was the father of Borukh (my grandfather) Chaim. It was he who took over the store. Once, in a conversation with my dad, I asked where he got his love for olives. Smiling a little, he replied: “In my grandfather’s shop at the entrance there was a barrel of olives, and when I entered there, I could always scoop a whole ladle out of it.” Childhood was happy; he was loved by both his mom Bluma and grandma Malka. From his childhood memories: he loved to comb his grandmother’s long hair.

He studied at the gymnasium, where education had a humanitarian direction: languages, geography, and history. A former officer taught mathematics. Knowledge was profound. I remember how one day my niece Irina, who studied Latin at the university, came to us, and they (she, having just passed the exam, and he, who studied Latin almost fifty years ago) recited Cicero in two voices “How long will you, Catiline, abuse our patience?” By the bar mitzvah (Jewish adulthood) he received a gift from Palestine, a chic multi-volume Jewish encyclopedia.

Growing up, my father became interested in the ideas of the youth Zionist movement Hashomer Hatzair (from Hebrew, “young guard”), created in 1916 as a Jewish analogue of scout organizations. There were branches of the movement in many European countries, including Romania. There was a cell in Briceni as well whose members were preparing for life and work in Eretz Israel.

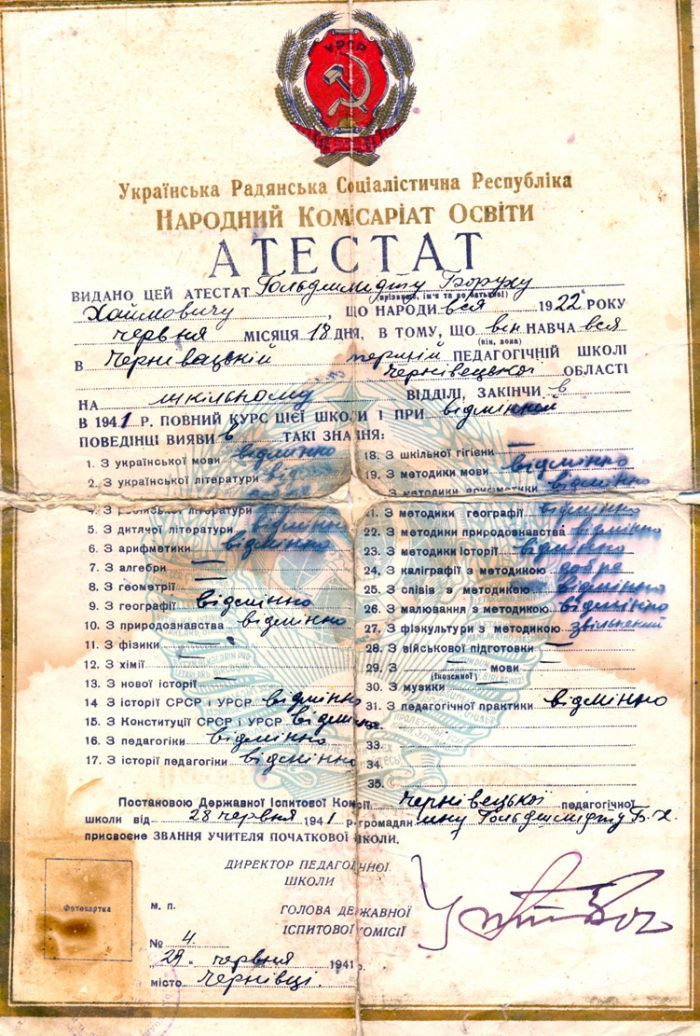

Сertificate of graduation from the Chernivtsi Pedagogical College

In June 1940, Soviet troops entered Bessarabia, and under the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, this territory became part of the USSR. For the father, this was a real shock, the collapse of all plans. He lay in bed for three days, experiencing what had happened.

Then the year 1941 came. Borukh studied in Chernivtsi at the Pedagogical School. There were many Bessarabian Jews there. In front of his eyes, NKVD officers were taking away his acquaintances, activists of the Zionist movement. Fortunately, this fate passed him, perhaps due to the war.

On June 28, Borukh fills out with his own hand a certificate of graduation from the Chernivtsi Pedagogical College and obtaining the qualification of an elementary school teacher. Why does he fill it out himself – because in the confusion of those days, the upcoming evacuation, the director gives him a form and allows him to do it. Note that the graduate did not overestimate himself a single note…

A week later, on July 5, Romanian troops entered the place.

Here it is worth interrupting our story and returning to Briceni to the Boruch’s family. On July 6, units of the Red Army left Briceni. From the fragments of the natives’ of the town memories about that period:

Yosef Horowitz “…Romanian military units entered Bricheni. It was Sunday evening, after a big rain. The next day, peasants from the surrounding villages broke into the town. On foot and in wagons, they dispersed throughout the shtettle, and looting began. They took everything that the eye could see and the hand could grasp. They left only the furniture. Beds, sofas, tables, chairs, wardrobes – all this was taken by the mayor’s office.”

Lev Bokal “… the pogrom immediately began. Shops, houses of wealthy citizens were smashed, all Jews that came to hand were beaten… We were immediately robbed: they took all the valuables from the house, money, documents, good clothes, dishes, a sewing machine.

… All the Jews were gathered at the synagogue and driven towards Transnistria. They didn’t let us take anything: no clothes, no money. A crowd of thousands of Jews from Briceni and the surrounding area was driven to the Dniester and transported to the other side, but they were categorically forbidden to stop in the villages…”

The ordeals began beyond the Dniester, where the earthly life of Borukh’s parents, and his grandparents ends…

Borukh is not taken into the army because of poor eyesight; he is evacuated to the Rostov region. Works as a clerk at a dairy farm in the village of Mishkinskaya. From the memories of that time: frequent bombings of low-flying fascist aircrafts, herds of roaring not-milked cows.

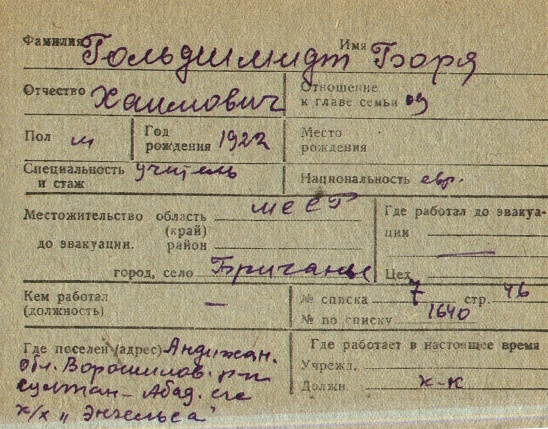

In October 1941, he ended up in the Andijan region of Uzbekistan, where he worked on a collective farm.

In February 1942, he became a student at the Kharkov Agricultural Institute, who was evacuated to the town of Kattakurgan. It is difficult to say what was decisive in this choice: hunger, loneliness, restlessness. It is only with great difficulty to imagine the feelings of a young man, torn from his usual environment, who did not know anything about the fate of his loved ones, who found himself in a completely different world, a world full of suffering.

In Kattakurgan, he joined the Weinzoff-Fishbein family, who had been evacuated from Ukraine. The head of the family Ikhil fought at the front. His wife Sophia worked as the director of an oil depot. A bottle of kerosene from the oil depot, sold by Boruch at the market, was a significant help to him in the meager student budget. Acquaintance with this family will be decisive for the further fate of a lonely Bessarabian boy. In August 1943, he marries Yasna Fishbein, who got out of besieged Leningrad.

Student at the Kharkov Agricultural Institute

In June 1944, the young family, together with the institute, returned to the liberated Kharkov. They often reminisced about this journey. The railway worked poorly, they had to wait a long time for the right train, theft flourished. At one of the stations, their suitcases were stolen. The thieves, however, were not lucky, there were just notes, and they out of anger scattered it all around the platform. The future agronomist had to collect his notebooks from the station.

After graduating from the institute in 1945, he asked for a job in Moldova and became the chief agronomist at the Orhei MTS (machine and tractor station).

They rented an apartment, my mother began to work in the district hospital, and my father spent all the time at work. It was the period of collective farms creation, he wandered around the villages. And he was only 23 years old. He had to learn a lot on the go.

Immediately, having arrived in Orhei, he went to Briceni, where he learned about the death of his parents. After he never comes to Briceni again. I often thought why, until finally understood, having stumbled upon the memoirs of Sh. Weisberg from Briceni: “For almost three years in the hell of Transnistria, the gnawing longing for the native Briceni did not stop for a single day. And here we are in Briceni. Pieces of former streets, burnt houses. In the very center, where Shvartsman’s and Spitzel’s stores used to be, is now a large place, covered with coal and burned with pieces of steel. Of the few remaining houses, dark holes gaped at us in horror—holes that had once been doors and windows. What about greetings from neighbors? Angry and frustrated; they didn’t even think we’d be back. And first of all, they were afraid of justice and retribution for the stolen.” Of course, such a collapse of hope and nostalgia, which in many ways supported and helped in the evacuation, such depression and confusion at the sight of emptiness and total loss of people, property, a sense of home and warmth that lingered in memory and soul, could not but cause a cold, sobering alienation, desire to forget forever, cross out and run away from places that were once dear to pain…

I was born in 1950. This fact did not affect my father’s attitude to work, from morning to evening he is there with rare days off. As I now understand, he did not know how and could not rest. The main thing was the work.

Offered an apartment, refused in favor of a worker with three children. He almost did not deal with me, but influenced strongly. I remember I was given a bird in a cage for my birthday, when my father came and saw the gift; he immediately released the bird into the wild. Or another case: in the 6th grade, I had to write an essay on the topic of who I consider a real person. I was going to write about him, but I was too shy. And one more vivid impression from the trip to the collective farm, I remember the silo tower, the attitude of the collective farmers towards him. I remember the shock received in the pioneer camp when we played tennis with him (I did not expect that he could, but it turned out to be from his childhood).

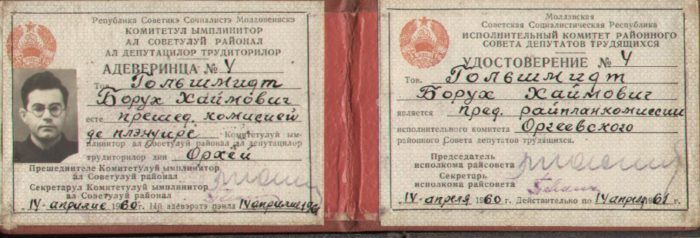

The position required membership in the Communist Party. They accepted him on the second attempt, the Briceni shop from the past “interfered”. In 1959, he became chair of the regional planning commission. It was a serious post, and Boruch, as usual, devoted himself to work. He smoked a lot, apparently, there was an addiction: he could not think about something without tobacco. The work was responsible – plans were distributed for collective farms. There were many who wanted to reduce their tasks. However, he was absolutely honest and fair. I remember someone brought a box of apples to the house, and I took it. There was an uproar. He preferred to spend his holidays with his relatives in Mogilev-Podolsky, his favorite pastime was chopping firewood.

Then there was a transfer to Chisinau, and work in the Council of Collective Farms. I remember a funny story that happened in Chisinau. He weekly bought the magazine Novoye Vremya (New Times) in Russian. Once it was not there, and dad was offered in French – he took it. The next time, only the German version was on sale – he took it also. The seller was very surprised. He didn’t know that the buyer’s questionnaire read: “…read and translate with a dictionary: French, German, read and speak: Yiddish, Ukrainian, fluent: Russian, Moldavian, Romanian.”

In 1979, dad fell ill; he was paralyzed on the right side of his body. But he could move around the apartment on his own, serve himself, maintain clarity of mind, read, type on a typewriter, communicate with his grandchildren, friends, neighbors. A moment etched into my memory from that period. He was visited by a friend from Orhei Moris Brunya. I go into the room; and two old Jews are sitting and talking in Romanian.

He survived his wife by 13 years and died in 1994. In June 2022, exactly in the month of his centenary, his great-grandson Daniel was born in Israel from his granddaughter Yasna. The life goes on, dad.

Efim Goldshmidt. Chisinau. Moldova