I didn’t see my grandparents. No one of them. Neither on my mother’s, nor on my father’s side. None of them took me on their laps, kissed me, pampered me with sweets, or walked holding my little hand in theirs. They did not experience the joy of my birth, my first steps, my first words. I didn’t even have a chance to put a stone on their grave, these graves simply don’t exist.

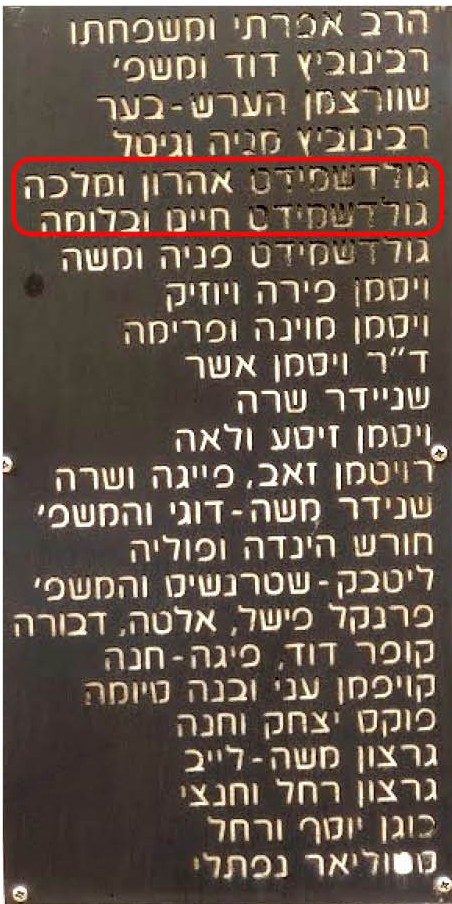

But now my son has found a place where we light funeral candles at the monument with their names. This is the “Southern Cemetery” in Israel. It is located in the southeast of the town of Bat Yam, on the border with Holon and Rishon LeZion. Here, among the steles of Holocaust victims from various European communities, there is a monument to the killed residents of Briceni and the surrounding area. The names of Goldshmidt Aron and Malka, Goldshmidt Chaim and Bluma are also indicated on it. These are the names of my great-grandparents and great-grandparents.

History of Researches

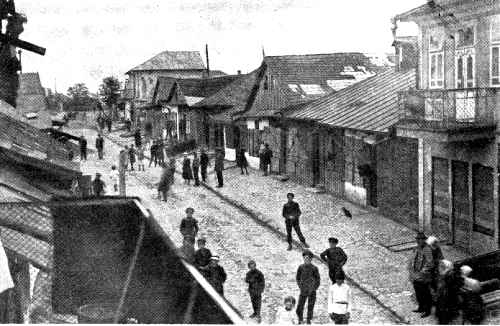

My paternal ancestors lived in Briceni, a small Jewish settlement located in the north of Bessarabia. Great-grandfather Aron was engaged in trade and owned a grocery store. He and my great-grandmother Malka had ten children. Normal life ended with the outbreak of war, when Romanian troops entered Briceni. A crowd of thousands of Jews from Briceni and the surrounding area was driven to the Dniester and transported to the other bank. Thus began their ordeals beyond the Dniester, where the earthly life of my ancestors ended…

The father, who returned from evacuation, learned nothing about the place and details of the death of his relatives. “Somewhere along the way they died…” And it seemed that this would forever remain a mystery to us. However, their great-great-grandson, Kirill, managed to find out information about their last days.

While researching the history of the family, in the Beit Ariel library in Tel Aviv, he discovered materials about the “Organization of Former Residents of Briceni”, which helped people from this town. The organization was created in 1951 during the visit of former Briceni resident Yosef Kessler (Kestelman), who lived in the USA and did a lot for his native Jewish community before the war and for the refugees from Briceni after.

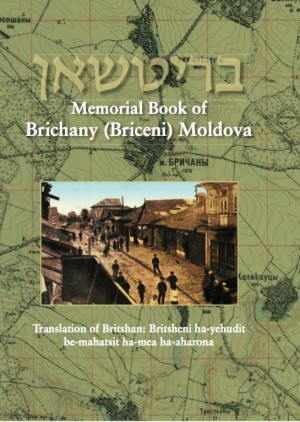

There, my son discovered the book “Briceni: Jewish Briceni in the First Half of the Century” published by this organization, edited by Yaakov Amitsur (Steinhaus), Michael Amitz (Cherkis), Shlomo Weisberg. The book, written partly in Yiddish, was published in 1964 in Tel Aviv and contained memories of the life, religion, residents of the town in the pre-war period, and memoirs of survivors of the war tragedy. In 2017, it was translated into English and published as part of the Book of Yizkor project by JewishGen. About 2,000 books were published in Hebrew and Yiddish to commemorate the destroyed Jewish communities.

“We don’t claim to make a perfect work; We are not professional writers, we wanted the book to be written by our compatriots, and not strangers, even professionals. We did not have documents that could serve as historical material. We relied mainly on our own memory. We tried to be precise. And we couldn’t delay publication any longer,” – is written in the preface.

And another quote from the book: “By the end of the 1930s, about 10,000 Jews lived in Briceni, who were mainly traders or artisans, especially furriers. The remaining 25% worked as intermediaries and in religious sphere. The flour mills of the wealthy Bershtein family and Joseph Babanchik were among the largest in Bessarabia. When Romanian troops occupied Briceni in 1941, Jews were forced to move to camps in Transnistria (across the Dniester River), and many were shot along the way. Others died from hunger, cold or disease. About 9,000 Briceni Jews were killed during the Holocaust. The number of those who escaped or survived in the camps was about 1,000 people.” You can learn about all this, about the interesting life of the Jewish community, its hard and bright destiny, from this book.

The Place of Death

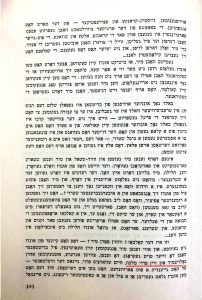

Among the memoirs published in the book is “Chronicle of Transnistria” by Yosef Horowitz, who witnessed the death of my ancestors.

“I remember that day very well and will remember it forever. It was Sunday evening, after heavy rain. …That same evening, at about 11 o’clock, terrifying screams were heard from different corners. The penal battalion arrived, dispersed to homes (of course, the best ones), kicked out the owners, and took away the beds and linen. The real “wedding” began on Monday at 8 o’clock in the morning, when peasants from the surrounding villages burst into the town. On foot and in carts they dispersed throughout the settlement and began plundering. They took everything that the eye could see and that the hand could grasp. Only the furniture was left. For this there was already the city hall. They sent prepared carts and completely emptied the houses: beds, sofas, tables…Only four walls were left.

…A day later, an order was received according to which all men aged 16 to 60 years old, under threat of death, must come to work every day at 6 a.m. The job involved unloading boxes of ammunition from vehicles. The work was very difficult, and there was no food. There was nothing to take from the house, no bread or other food – everything was stolen.

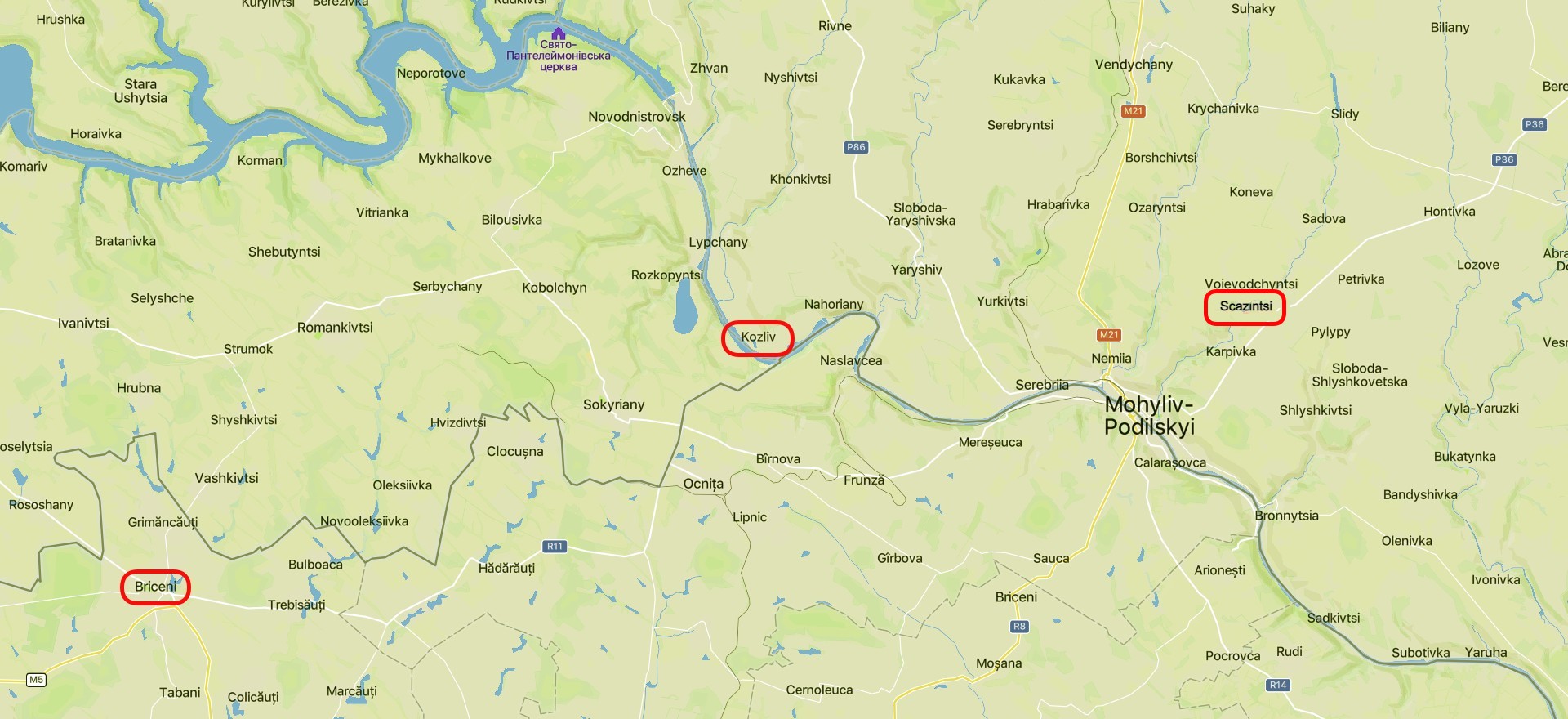

Soon it became known that we would be expelled. There was great panic. People started running like crazy just to get some food. We spent our last money to get some flour and bake anything. On Monday, July 28, at six o’clock in the morning, Romanian gendarmes knocked on all doors to inform that everyone needed to come at eight o’clock to the fire station area. They picked up the entire population, did not leave a single child in the cradle, took the mentally ill and epileptics out of the hospital – and the march began.

In Kozlov, on the other bank of the Dniester, where we came, we were sitting in a pigsty and we were all dirty and full of lice. Who knows what would have happened to us if, God forbid, we had stayed there for a week. The regime there was very strict: we were not allowed into the village; we were simply starved to death. There was a Romanian officer there who loved money, and he gathered about 300 people (who, of course, paid well for it) and decided to send these unfortunate people, in his words, to a collective farm to collect grain from the fields. He even provided peasant carts for the elderly and sick. Where is the collective farm? Where were we going? None of us knew the answer. That’s how we arrived in Skazinets. Many residents of Briceni met their death here. Here, among others, Aron Goldschmidt died along with his wife Malka, as the wife of Chaim Schwartz; the hatter Neigas – wounded his leg while walking and was shot. It happened more than once that someone went to the village for food, and when he returned, he no longer found anyone from his family…”

This is how the village of Skazinets in the Mogilev-Podolsk region in Ukraine appeared for us, the place of the last breath of our loved ones…

Continuing the Search

The search for the family traces along the roads of history led Kirill to the Archive of Ghetto Fighters. There were photographs from 1980 of a cenotaph (in Greek) or andarta (in Hebrew) – a monument similar to a tombstone, but installed where the remains of the deceased are not contained, a kind of a symbolic grave. It was placed by the same “Organization of Former Residents of Briceni” at the cemetery in Bat Yam. There are many such “andarts” on it in memory of the fallen Jews from different communities in Europe. The cemetery occupies a large area and does not have a digitized catalog of such memorial signs. This made the search difficult. Long inquiries into the administration led nowhere. The Arab servant Salem, who thoroughly knew the entire cemetery, came to the rescue. It was he who brought us to the goal. The memorial consists of two steles with 24 marble plaques, on which are engraved in Hebrew the names of the residents of Briceni and the surrounding area killed during the Holocaust. One can imagine how difficult it was to collect information about the victims, and how much work was done to establish their names.

My great-grandfather Aron Goldschmidt and his wife Malka had ten children, five daughters and five sons: Miriam, Yiheskel, Tanya, Sonya, Olya, Yankel, Chaim (my grandfather), Meyer, Chana, Israel.

Currently, the youngest bearer of our surname in the male line is my son Kirill. I am proud that he wears it, and I believe he will continue wearing it, with dignity.